Despite declining enrollment, school buildings in the Grants Cibola County School District are in need of serious repair, according to a 68-page report from the Legislative Education Committee in Santa Fe. The local economy has contributed to the loss of students at GCCS. The ailing infrastructure at GCCS is comparable with statewide decay of educational institutions, but GCCS has seen a slightly sharper increase in decay at school buildings than the state average.

Student enrollment has dropped significantly at GCCS. In 10 years, GCCS enrollment has dropped 13 percent, a loss

“About half of all schools in [Grants-Cibola County School District] have a [Facility Condition Index] above 60 percent, suggesting demolition and replacement may be a more cost-effective option than renovation. The remoteness of many schools in both districts presents challenges to maintaining and updating infrastructure.”

of 461 students, from School Year 2012 to 2022. This decline in enrollment is compounded by a number of issues, the high decrease in enrollment numbers comes even though there are no charter schools in Cibola County. With no charter schools, what is driving the loss of students? The report places the blame on three things: COVID-19, Declining birth rates, Outmigration.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the already steady trend of population loss in Cibola County. The report claims that many students left public school to enter private homeschooling programs during the worst of the pandemic, “How-

Courtesy ever, preliminary 40th day school district enrollment counts indicate some students are returning to the districts. In [Fiscal Year 2023] in [GCCS], enrollment grew by approximately 300 students,” showing that the pandemic’s effects on school enrollment are not permanent. The area economy has been a major factor in GCCS’ loss of student enrollment.

Birth rates are declining across the country, that loss is felt in New Mexico. The report declares, “According to the University of New Mexico’s Geospatial and Population Studies program, San Juan and Cibola counties are projected to lose population by [nine] and [five] percent, respectively, from 2020 to 2040. A 2020 report from the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education projected that from 2019 to 2037 the number of high school graduates in New Mexico will decline by 22 percent due in part to declining birth rates representing one of the steepest declines in the country.” The issue is not just that less young children are being born in Cibola County, but that the economy has not been strong enough to help support families with young children, causing many families to leave in what is called “outmigration”. According to the report, “In nearly every year since 2011, more individuals have moved out of both San Juan and Cibola counties than have moved into them,” due largely to economic hardship. “In 2020, the Escalante Station, a coal power plant near Prewitt, New Mexico, closed with a loss of 107 employees. Grants district officials report 100 of these jobs were from Cibola County. The Ciniza Oil Refinery in Gallup closed the same year, resulting in a loss of 200 jobs but it is unknown how many of these jobs impacted Cibola County. Similar to in Central, these closures impacted the ability of Grants to generate local revenue.”

Decaying School Infrastructure

The economy is not the only thing hampering the development and growth of local school infrastructure.

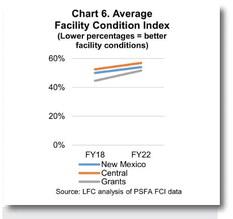

The statewide average for school age is 36 years old, according to the LEC report. The average age for a school building in GCCS is 37 years old, putting the state on track to follow statewide trends. To determine the need for educational facility repair in the state, New Mexico has an origination called the Public School Facilities Authority that tracks the condition of school buildings. PSFA uses a metric called the Facility Condition Index, the higher the score on the index, the more expensive the school would be to repair versus complete demolition and reconstruction. The report states, “About half of all schools in [GCCS] have an FCI above 60 percent, suggesting demolition and replacement may be a more cost-effective option than renovation. The remoteness of many schools in [GCCS] presents challenges to maintaining and updating infrastructure.”

There is a wide discrepancy in the current state of school facility management. Los Alamitos Middle School scored a 16 on the FCI, while Bluewater Elementary scored an 85. This assessment was made even after GCCS received $5.5 million for facility repairs at Bluewater Elementary.

The report states that, thanks to a lawsuit called Zuni v. State of New Mexico, a special fund was created to establish a matching fund for school districts to repair their facilities. School districts will receive a match for repairing their schools, so no single district suffers a heavy cost from repairing a school; the only time a school district has to pay out of their own pocket to make repairs is when the school receiving repairs does not have a high enough score on the FCI.

While GCCS has roughly followed statewide trends in terms of facility decay, it has seen a spike in decay compared to the rest of the state. In Fiscal Year 2018, the statewide average was at 45 percent of schools in need of serious repair, In Fiscal Year 2022, the statewide average was 54 percent. In FY2018, Cibola’s average for schools in need of serious repair was 43 percent, by FY2022, the percent had increased to 52.

Schools in Cibola are above the threshold of repair, and it would be cheaper for many of them to be demolished. The report specifically notes Bluewater Elementary, which is in such disrepair the report states, “demolition and replacement may be a more cost-effective option than renovation.”

In his letter responding to claims by the LEC, Superintendent Max Perez did not mention the claims made about decaying school infrastructure.