My life has a geographic dividing line - the Mississippi River - with almost four decades living east of the mighty river and more than 30 years in the West.

Most of my life has involved livestock. Cattle producers east of the Mississippi are called beef or dairy farmers depending on which breed they raise. Those to the west are ranchers unless they specialize in dairy operations.

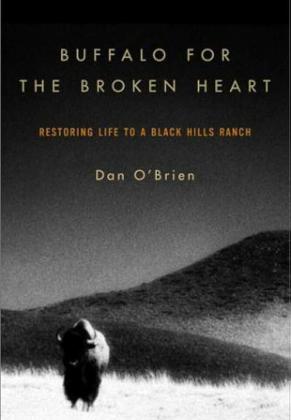

One of my favorite books, Buffalo for the Broken Heart, came to mind when I was thinking about Cibola County, N.M., where I lived for many years. A bison is the official seal of Cibola County, which was founded in 1981.

Two species of bison flourished in North America long before humans arrived. Large herds roamed through shoulder-high native grasses in their annual migrations across this part of the Southwest for centuries.

'The word Cíbola is Spanish for 'female bison' (usually called 'buffalo'). It's interesting to note that the buffalo never came west of the Río Grande [River] to the area we generally consider Cíbola,” wrote historian Abe Peña in his book, Memories of Cibola.

The Spanish conquistadors were followed by other immigrants who decimated the bison.

The 1862 Homestead Act, signed by President Abraham Lincoln after the southern states seceded, allowed any adult citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. government to claim 160 acres of surveyed government land. Ten percent, 270 millions acres, of the U.S. was “claimed” under this act, which did not acknowledge Native American “ownership.”

Cattle production became a sign of “civilization” to European immigrants who sought a new life west of the Mississippi. By 1866 Texas ranchers were utilizing the Goodnight-Loving Trail for herding open range cattle from Young County north along the Santa Fe Trail, crossing Raton Pass into Colorado and heading to Cheyenne, Wyoming. All those hungry animals destroyed much of the native forage that had sustained the bison for centuries.

Author Dan O’Brien’s life on his South Dakota ranch more than 150 years after the Homestead Act illustrates the consequences for modern ranchers.

O’Brien struggled for twenty years to make ends meet on his cattle ranch, Broken Heart.

“Trying to make a life as a cattle rancher in the economy of the Great Plains makes for a lot of driving, and one late afternoon a dozen Septembers ago it led me to a remote dirt road along the southern boundary of Badlands National Monument. I was thinking about the mortgage payment that would be coming due in October, and the recent, inexplicable dip in cattle prices that would cut my income in half. I drove too fast, and when I came over a dusty rise I nearly ran into an enormous bull buffalo. He reclined luxuriously in the center of the dirt road, stretched out in the sun like a two-thousand-pound tomcat,” recalled the author.

And then one year a neighbor invited O’Brien to help with the annual buffalo roundup. That caused him to re-think cattle ranching. He changed to raising bison, which are native to the Great Plains.

O’Brien started with thirteen calves that looked like “short-necked, golden balls of wool.” This small herd was the first time in more than a century and a half that buffalo had grazed his land. More than a few neighbors questioned his decision to quit traditional ranching.

He responded by pointing out that cattle ranching is an alien economy in the context of the Great Plains. It is environmentally devastating and anachronistic.

“The difference between cattle and buffalo is obvious enough for anyone to see,” he explained. “Buffalo require little water, are less picky eaters than cows, and move around as they browse, so they don’t graze a patch of grass down to the roots.”

This book features entertaining sketches of the author’s human neighbors, wry comments about visitors skeptical of his new endeavor along with his vision for the future of the bison industry.

“Buffalo for the Broken Heart” chronicles the author’s early years raising buffalo. The market was still highly volatile in the late 1990s when O’Brien left cattle ranching and turned to raising bison. The author’s insight into the rhythm of life on the Great Plains highlights the importance of the natural environment and human responsibilities.

Sidebar:

O'Brien, a native Ohioan, graduated from Findlay High School, earned an undergraduate degree from Michigan, and a Master’s from the University of South Dakota, then a Master of Fine Arts at the University of Ohio, a PhD from Denver University, Colorado, and worked as an endangered species biologist for the South Dakota Department of Game Fish and Parks, and later worked for the Peregrine Fund. He began to change his small cattle ranch in South Dakota to a buffalo ranch in the late 1990s. His experiences helped establish the Wild Idea Buffalo Company and Sustainable Harvest Alliance in 2001. Dan and Jill O’Brien raise buffalo and live on their 9,000-acre Cheyenne River Ranch in western South Dakota.